Inside the ambulance: lives of people who run UVAC

By Aliya Uteuova

Maine Campus

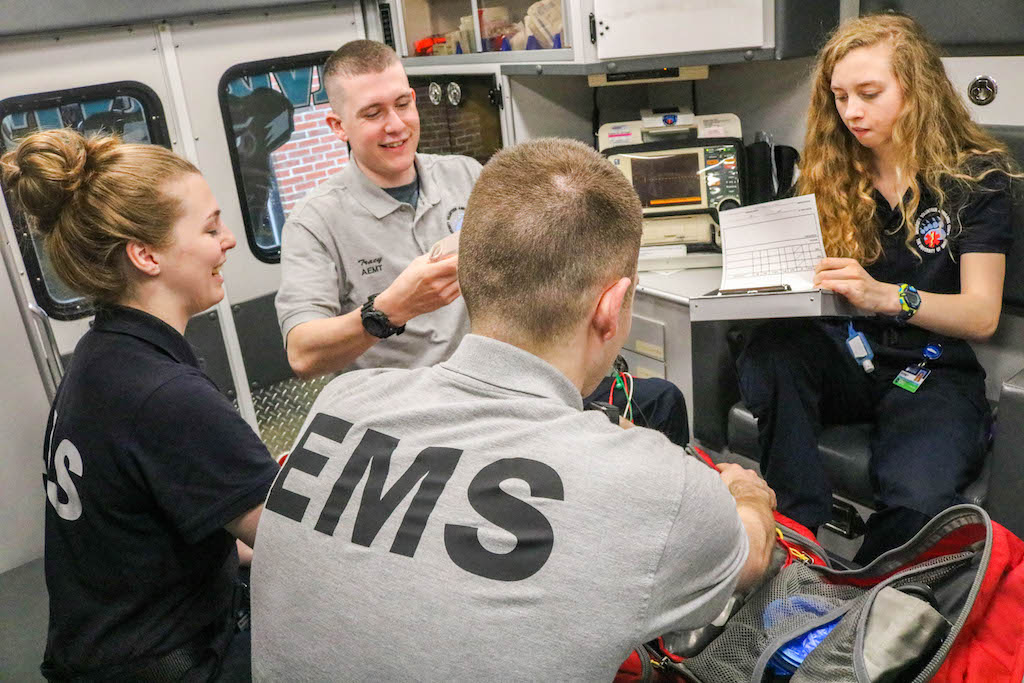

Four University of Maine students share what it’s like to be volunteer EMTs at a college campus

As you rush to class every morning, you probably found yourself walking behind a student with EMS letters on the back. Walking by the Cutler Health Center, you might catch a glimpse of a white and blue ambulance. A student in a navy blue uniform with EMS letters and a walkie-talkie in his belt just finished washing the car, cleaning the words that read “University Volunteer Ambulance Corps.”

The University Volunteer Ambulance Corps, also known around campus as UVAC, is the on-campus emergency medical service (EMS) for the University of Maine. UVAC responds to emergency calls at UMaine as well as providing back-up aid to surrounding towns. The ambulance service is entirely student-run, and it is mostly undergraduates who carry the equipment and master the techniques necessary to provide the highest level of pre-hospital care.

“I didn’t know what I wanted to do in college,” Jacob Sol, a fourth-year forestry student, said. “I come from a blue-collar family. UVAC was tabling when I was doing a freshman tour, so I got involved and liked the sense of community.”

Sol grew up watching his mother provide medical care as a certified nursing assistant. A good part of his childhood was spent in nursing homes, where he got to watch his mother interact with patients. Sol’s father worked at a power plant where he saw people get injured.

“I was a clumsy, rambunctious, kid,” Sol said. He believes that his parents influenced his decision to join UVAC. “I would hurt myself a lot and my father was always there to take care of me. He kept his cool because he could handle emergencies.”

Sol has been a member of UVAC since his first year at UMaine. He progressed through the different branches of the department, from being only on the volunteer crew to leading each of three UVAC’s managerial staff: operations, relations, and university training safety. The “V” in UVAC stands for “volunteer,” but for heading each of the three departments, students are granted a stipend. There have been talks in the past to make the volunteer EMS positions paid.

It is expected of all members to sign up for 24 hours of volunteer shifts per month. But almost everyone works more than that.

“Most of us way exceed that and do 100 hours a month,” Nate Tracy, a third-year political science student, said. Tracy has been in UVAC for three years. His father was a police officer, and ever since Tracy was a child, he wanted to be like his dad.

Growing up around that shaped Tracy’s view of first responders. “They are a decent folk, with a calm demeanor. They would joke around but also knew how to take things pretty seriously when needed.”

These qualities resonate in Tracy as he naturally humors fellow UVAC members, remembering to check the red bell in the lounge area every now and again.

The bell rings whenever UVAC is called, indicating help is needed.

“When you hear the bell ring you get that rush of fear and think, ‘What am I gonna do?’” said Sol.

Ryan Lavway, who joined UVAC his first year at UMaine, said “In the field, I’ve had some of the most critical patients when I’ve been by myself, in control of the situation.”

Lavway hoped volunteering with UVAC would tie in nicely with his nursing major. EMT classes he took in high school put him ahead of other volunteers, since UVAC members aren’t required to be licensed EMT’s their first year at the corps.

Surprisingly, alcohol- and drug-related incidents make up only around 20 percent of all the calls UVAC receives throughout the year. The rest are standard medical calls for injuries, accidents, as well as calls for standby medical assistance in fires and every time the fire alarms are pulled.

Once Lavway treated severe anaphylaxis — a severe systemic and allergic reaction when a person’s throat closes and they don’t have any air exchange. This can happen to people who are severely allergic to peanut butter.

Another memorable call Lavway responded to was for ventricular tachycardia (V-tach), a life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia. He performed a standard protocol he was trained for and the patient’s heartbeat stabled, so Lavway didn’t have to shock the patient with a defibrillator.

All members of UVAC have to follow the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). The federal legislation that provides data privacy and security provisions for safeguarding medical information. HIPAA insures ensures that student volunteers who might be treating their fellow classmates do not release any confidential information.

We can’t release information to the police, and we don’t talk to students we treated unless they talk to us,” Tracy said. “I’ve had a few patients come up to me and say: ‘Hey thank you for taking care of us.’ It’s nice that they’re going out of their way to thank us.”

Tracy, Lavway and Sol have all completed well over 1,000 hours this year.

Those are just the scheduled hours we worked,” Sydney Green, a third-year biology student, said. “But the actual hours we spend here are more.”

For Green, who volunteered over 900 hours this year, separating herself from the office where she works, takes breaks, does her homework, and often naps, is the hardest part of being in UVAC. “You do want to be down here so much, but this is like a full-time job.”

Green is no stranger to the emergency room. She remembers vividly the time she got stitches at the hospital. “It was really cool that they can sew your body back together,” Green said.

When she got to college, she didn’t know what she wanted to do, but she did know that she wanted to help people.

There’s a running joke between the volunteers that the UVAC office is their primary home. Google Maps in Tracy and Lavway’s phones shows UVAC as their primary home, and their apartments as their work. Despite that, Green and the rest of the crew, agrees that providing the care they do is not monetized for a reason.

“When you have the volunteers, you find people who have the true heart for it,” Sol said. “Leadership positions can benefit the heart and soul of people who have it vested.”

Sol is the student chief of UVAC, meaning that he supervises all three departments, which are headed by individual chief officers.

“That’s the incentive, every one of the officers proved that they’re willing to help people,” Tracy said. He is the current captain of operations and next year’s assistant chief. He cannot envision his future anywhere other than public service. Whether it’s law enforcement, or firefighting, Tracy could never sit behind a desk.

“I have a 30-second attention span,” Tracy said. Over the course of his service, like many other volunteers, he has learned efficient napping skills that allow him to be alert for his nightlong duties. “I like high intensity, being able to go out and get into a truck and go somewhere. I get a front row seat and not watch life go by.”

This article originally appeared at: https://mainecampus.com/2018/05/inside-the-ambulance-lives-of-people-who-run-uvac/