EMS Ready Campus Application Guidance

The following information is designed to provide additional guidance or resources for certain application steps. It is organized by the Tier, then by the application section or application step. Not all sections or steps have additional guidance. There is also a separate FAQ page, and the main program page contains links to generic resources that are not specific to any one Tier.

While you read through the guidance and complete the program steps, remember that EMS Ready Campus, like all NCEMSF self-evaluative programs, is designed to help organizations on a path to improve their operations. As such, perfection in all areas (especially in regards to plan development and exercise design and execution) is not essential. Recognition will still be granted even if areas for improvement exist in the submitted applications, and NCEMSF staff can be contacted via emergency.management@ncemsf.org at any time during the process to provide mentorship and guidance.

Bronze Tier

Tasks in the Bronze Tier are intended to introduce EMS agencies to emergency management. The requirements for this tier will serve as the foundation for higher tiers. While the program staff may be more lenient on the requirements for the Bronze Tier than they are for higher tiers, feedback designed to improve application components will still be provided and organizations should act on that feedback to improve their operations.

ICS Training

The Bronze Tier requires that all staff take three FEMA courses, all of which are available online as free independent study classes.

- IS-100.c: Introduction to the Incident Command System, ICS 100

- IS-200.c: Basic Incident Command System for Initial Response, ICS 200

- IS-700.b: An Introduction to the National Incident Management System

Those who have taken earlier versions of these classes (with different suffixes) may submit those courses in lieu of the current editions.

Components of a Mass Casualty Incident Plan

The following is intended to provide guidance on drafting a Mass Casualty Incident (MCI) plan. Utilize these recommendations to help you create a plan (or revise an existing plan) to best be able to respond to incidents on your campus. Please remember that the steps below are general guidance. Your specific plan should meet the individual needs of your organization, and comply with any requirements, regulations, and/or laws from your institution, local jurisdiction, region, and state. As such, the items below are not a check-list by which your plan will be accepted or rejected when submitting your EMS Ready Campus application, but application evaluators will look for many of these elements and may provide corrective feedback if certain elements are missing.

As with all emergency management planning, drafting an MCI plan should be a collaborative process. Before beginning, you must identify a planning team made up of subject matter experts who can assist with the process. These individuals should not just come from your organization's leadership team but should also include representatives from outside agencies you would work with during an MCI, campus administration, hospitals or medical direction, and any regional or state EMS coordinating bodies. By soliciting outside input, you will ensure your plan does not conflict with other outside plans, procedures, regulations, or laws.

A good MCI plan should have a realistic scope. What is an MCI for your agency? What goals and objectives does your agency have when responding to an MCI. How do the abilities and resources of your agency fit into the larger EMS picture for your area? By setting expectations, you can ensure that your plan does not exceed the available capabilities of your squad or your regional partners.

Your plan should include guidance on when an MCI would be declared versus when normal operations would be used. This guidance is called activation triggers. Some agencies chose to set defined numbers or types of patients that would trigger an MCI, while others may decide to use looser definitions. For collegiate EMS agencies that have reduced response capacities during certain portions of the academic year, variable triggers or looser definitions (for example, based on the number of in-service units) may be more appropriate than an across-the-board trigger based only on number of patients.

Because MCIs are different than normal EMS responses, the on-scene organizational structure also needs to change. Your MCI plan should address the specific roles and responsibilities at an MCI along with who is expected to fill those roles. Be sure your plan can stand the test of time by assigning roles not to specific individuals or even by the rank or role in your organization's day-to-day command structure, but rather by assigning roles based on categories like "first-arriving EMS unit" or "first arriving outside agency supervisor." This gives the plan enough flexibility to be applicable in a variety of scenarios while still providing enough guidance to responders that they can know their expected roles.

Only after addressing the issues described above should you come to what most people think of when they see an MCI plan: triage, treatment, and transport procedures. It is best to follow established algorithms and existing best-practices in these areas. Consulting with regional or state EMS coordinating bodies can ensure your triage methods are consistent with the rest of the responders you will work with. When considering treatment, your medical director should provide input on allowed deviations from normal practice (such as rapid extrication). Your treatment section should also consider situations where there will be extended on-scene treatment needs, and how those needs can be addressed. Transport considerations will depend on available on-campus and mutual aid resources, the capacities and locations of area hospitals, existing regional or state-wide plans for transport from MCIs, and access to other specialty resources (air ambulances, medical ambulance buses, and public transit, school, or shuttle buses).

Emergency management planning does not stop with the incident. A section on demobilization procedures will address what to do after all patients are transported. This should include compliance with documentation requirements, cleaning or replenishment of equipment, and even post-incident mental health concerns for responders.

Finally, there are three administrative items that should be included in your plan: after-action analysis procedures and a timeline training on the plan, and a process for plan revision. After-action analyses should take place once the incident is fully concluded and should be conducted in a "no-fault" manner. Ideally, having a moderator with experience in the AAR process who was not directly involved with the response will ensure that the process proceeds smoothly. Responders should discuss what went well along with areas for improvement. Notes should be taken, and leadership should take identified areas for improvement and create a list of improvement actions (specifically noting steps to be taken, who will take those steps, and when the steps will be completed by). In addition, your members need to know what is in the plan prior to implementing it. The plan should specify when and how training will be conducted. Training should always occur before the plan is used in an exercise, as this gives everyone the best possible chance of successfully implementing the plan and allows your exercise to highlight weaknesses in the plan (as opposed to exercising before training, which will only show you that training is needed). Finally, the plan should include guidance on how often revisions should take place. Plan revisions should incorporate lessons-learned and improvement steps from exercises and real-world activations. The process should also look for any changes inside your organization, at mutual aid partners, with laws or regulations, and to best practices as all of these can affect components of the plan. If the overall situation or environment in which the plan would be used changes, the plan must change too.

For additional information on the emergency planning process, please reference a FEMA document titled Comprehensive Preparedness Guidance 101 (CPG 101) which specifically covers developing emergency plans in general, as well as their guide that is specific to Emergency Operations Plans for Institutions of Higher Education.

Hazardous Materials Information

There is a federal law called the Community Right-to-Know Act, which requires any organization that stores certain quantities of hazardous materials to file reports on those chemicals annually. These reports are commonly called Right-to-Know reports or Tier 2 reports. They are usually filed with the EPA, a state environmental agency, and/or the local fire department or emergency management agency. Most institutions of higher education have their risk management or safety offices complete the reports. These reports should not be confused with Cleary Act disclosures of campus crime data and safety issues. While access to that information is also important, only the hazardous materials data is required for the EMS Ready Campus application.

In addition to the Right-to-Know/Tier 2 hazmat reports (or in lieu of them if your state does not authorize disclosure of them), you are also asked to document how your responders can access additional information on hazardous materials present on your campus. The Right-to-Know/Tier 2 reports only cover chemicals over a certain quantity that are stored for a certain length of time. Most campus labs use quantities under the reporting thresholds or use their chemical stocks too frequently to be considered to be storing them. As such, you should find out how you can access Safety Data Sheets on chemicals used on campus or other systems (like chemical storeroom lists) that can provide you with data on chemical hazards that may be present. Safety Data Sheet (SDS) access is ideal, because those documents also include the physical properties of the chemical and specific response procedures. However, access to at least an internal system tracking the types, locations, and quantities of chemicals can provide you with enough information to plan for special hazards should they exist.

Hazard Vulnerability Analyses

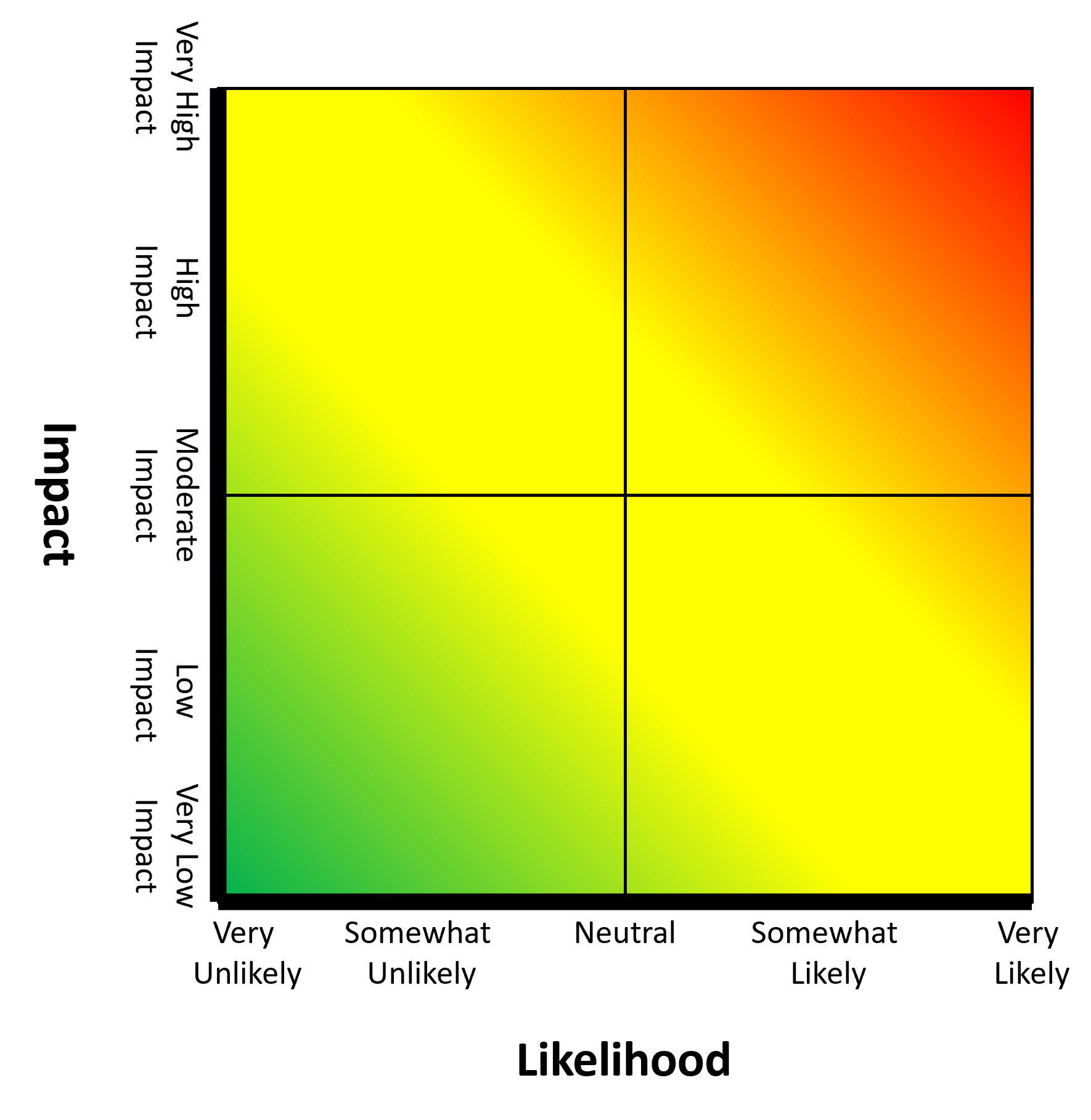

A Hazard Vulnerability Analysis (HVA) is a document designed to help organizations assess hazards that they face and prioritize them based on both likelihood and impact (consequences). Likelihood means the chance that your campus could be affected by a hazard, regardless of how “bad” the hazard is. For example, thunderstorms may be very common (i.e. have a high likelihood) in many areas but may not have significant impacts. Impact refers to the severity of the hazard were it to occur on your campus. While there are a multitude of factors that affect impact, you should select the level of impact you feel is most applicable to your campus’s general operations.

A Hazard Vulnerability Analysis (HVA) is a document designed to help organizations assess hazards that they face and prioritize them based on both likelihood and impact (consequences). Likelihood means the chance that your campus could be affected by a hazard, regardless of how “bad” the hazard is. For example, thunderstorms may be very common (i.e. have a high likelihood) in many areas but may not have significant impacts. Impact refers to the severity of the hazard were it to occur on your campus. While there are a multitude of factors that affect impact, you should select the level of impact you feel is most applicable to your campus’s general operations.

These two factors (likelihood and impact) are the components of risk. While some formal HVAs may also include weighting factors to produce risk scores, it is also possible to just use the categorization of likelihood and impact to group hazards. Imagine you are plotting hazards on a graph, where the X-axis (horizontal axis) is likelihood from least likely to most likely and the Y-axis (vertical axis) is impact from lowest to highest. Hazards that are both high likelihood and high impact are the ones that pose the greatest risk and would fall in the top right corner of the graph. Hazards that have either high likelihood and low impact or high impact and low likelihood are of moderate risk and would fall either towards the top left or bottom right of the graph. Hazards that are both low likelihood and low impact would be low risk and would fall on the bottom left of the graph.

When completing the HVA Worksheet at the Bronze Tier, you are also asked for how you selected the hazard for inclusion in your HVA. Potential options include the fact that the hazard was noted in the official campus Hazard Vulnerability Analysis or other similar document, the hazard was noted by campus emergency management or risk management as one for inclusion, as a result of your research, or as a result of your agency’s review of past responses.

It is also possible to do this HVA activity specifically for special events, but that is not covered by this program's requirements.

Continuity of Operations

The first step in continuity planning is to identify what your organization does, and what needs to continue to happen to meet your organization’s mission, goals, and objectives. While most EMS agencies could very easily put “patient care” or “responding to calls for service” on this list, there are also numerous other behind-the-scenes activities that take place that are necessary for these outward-facing tasks to be successful. Please note that especially at the Bronze Tier, you are not expected nor required to have a comprehensive list of these tasks to successfully complete the EMS Ready Campus program. Instead, reviewers will be looking to see what tasks you identified and will usually provide feedback on how to continue to improve this listing. This is covered by requirement B.G.1.

Once key tasks have been identified, B.G.2 asks you to document who is responsible for those tasks. There is usually someone with Primary responsibility as well as one or more people with Supporting responsibility. Consider two examples.

- The EMS Director may have primary responsibility for submitting the state EMS organization license renewal. They could be supported in that role by the Medical Director (who provides copies of protocols), the Operations Officer (who confirms the list of equipment and vehicles), and the Administrative Officer (who assists in writing the application). In this example, the EMS Director has primary responsibility and the Medical Director, Operations Officer, and Administrative Officer all have Supporting responsibility.

- Each Crew Chief is tasked with reviewing all patient care reports from the previous shift for completeness as well as performing a first-pass review for any quality control issues. While there are other people who might be necessary to this process taking place (the previous shift’s staff need to have written reports in order for there to be reports to review, the Medical Director needs to have protocols/SOGs for there to be quality assurance standards to meet, etc.), none of them are directly responsible for the task of reviewing reports. Therefore, the Crew Chief (as a position, not a specific person) has Primary responsibility, and there are no individuals with Supporting responsibility.

At this point, you will be ready to begin identifying continuity steps. In order for key tasks to continue, we need to know what happens if individuals (by name or position) are not available. Who assumes their duties? Because the answer to this question often changes task-by-task, it is helpful to delineate this on a task-by-task basis as required by B.G.3. We now return to the two tasks above (EMS organization license renewal and daily patient care report review).

- In the case of submitting the state EMS organization license renewal, if the EMS Director is not available, someone else will need to assume that role. Usually, submission of a state EMS organization license must be someone who can act in an official capacity for the organization, and the administrative rules at institutions of higher education may place further restrictions on this. It will be up to you to determine who can fill this role. Sometimes, the Medical Director can step in. Other times, this authority could be delegated to a Captain or Chief (student). In other cases, the authority needs to go to someone outside of the EMS organization (health services manager, public safety department leader, etc.). But regardless, knowing who can step into that role in an emergency will ensure that the license renewal is submitted on time and the organization can continue to operate.

- In the example of daily patient care report review, your options may be different. If there are multiple Crew Chiefs, then in the absence of one the others might be able to step in. But what if someone else were needed? In that case, the person who steps in would need to have working knowledge of the report review process, they would need access to the report-writing system to access the necessary data, they may need additional training on handling of confidential medical records, and they could also need training on the quality assurance process. Given this range of skills and duties, would the backup to this role be a single person, or could the duties be split amongst more than one individual?

Once you have answered these questions, you have taken the first steps towards continuity planning: determining key tasks and lines of succession. Repeat this for your group’s major tasks and responsibilities. You may use the worksheets on the NCEMSF website or other templates (for example, from FEMA or from your own campus’s COOP program).

Supply Chain

A supply chain is the interconnected network of companies that work together to fulfill orders for particular products or services. In the case of medical supplies, this network includes the medical supply companies you purchase supplies from, the manufacturers who make those supplies, and even the companies that make or transport the materials required for the supplies themselves.

In 2017, Hurricane Maria caused significant damage in Puerto Rico, the site of factories that produced the vast majority of the IV fluid bags used in the United States. Healthcare companies were paying increased prices for a significant length of time until additional manufacturing capacity was restored.

When evaluating your medical suppliers for supply chain weaknesses, look for key areas such as:

- Supplier only carries one brand of a particular product (medication, IV catheter, etc.), meaning that they cannot substitute an alternate product if the primary is not available.

- Supplier does not carry stock of an item in its own warehouse, and instead relies on a direct shipment (sometimes called a drop shipment) from the actual manufacturer.

- Supplier indicates that certain products are only available in limited quantities, which means that they might not be able to support larger orders in the event of an emergency or disaster.

- Supplier only uses one shipping company (UPS, FedEx, etc.), which would put deliveries at risk if the shipping company experienced an issue.

- Supplier only uses a single warehouse or distribution center, which puts them at risk for local disaster impacts at that warehouse which could delay delivery of medical supplies.

Silver Tier

The Silver Tier builds on the work done at the Bronze Tier. In addition to the added requirements, be aware that evaluation of the EMS Ready Campus applications for the Silver Tier will be stricter, and the program staff may ask for additional revisions prior to granting the recognition.

Notifications

Most EMS agencies will not have direct access to the campus mass notification system. However, EMS may have a need to send an alert to members of the campus regarding an urgent situation or public health issue. For example, EMS crews may arrive on scene of a motor vehicle incident and find that there has been a chemical release that requires a shelter-in-place. In these situations, what process would you follow to request than alert be sent? This will in most cases require an intermediary (police dispatcher, emergency management, etc.). In your response to S.A.3, provide the appropriate documentation on how this process works.

Training

Remember that anyone who has joined your organization since the Bronze Tier training was conducted must also complete all Bronze training requirements.

ICS Training

One additional free online FEMA class is required for the ICS training at the Silver Tier.

Those who have taken an earlier version of this class (with a different suffix) may submit that course in lieu of the current edition.

Hazardous Materials Training

In addition, the Silver Tier requires training in Hazardous Materials Awareness. This training should meet the requirements set out by NFPA 470 (formerly 472 and 1072) or the HAZWOPER (29 CFR Part 1910.120) regulations. A free online version that meets NFPA requirements is available from the Texas A&M University Extension Service.

Other universities may provide similar online courses, or an in-person class may be available. When providing documentation for this requirement, in addition to the training roster or individual certificates, please provide information showing that the class meets the NFPA or HAZWOPER requirements.

All courses at the Hazardous Materials Awareness level require access to the Emergency Response Guidebook. This should already be available to you as an emergency response agency; copies are normally placed in all emergency vehicles. Hard-copy versions are produced every four years (on the same schedule as US presidential elections). If your organization lacks these books, contact your local fire department or emergency management agency for information on ordering copies in your region. For the purposes of the class, you can also access a PDF version of the current edition at the PHMSA website. Various phone app versions are available as well; PHMSA publishes an official app version (accessed from the PHMSA website).

Additional Training for Leadership

Additional training is required at the Silver Tier for anyone who may assume a command role on an incident scene as well as listed members of your organization's leadership team. Based on the content of the courses and your organization's internal procedures, you may also wish to assign these courses to additional members as you see fit. These are all free online FEMA classes.

- IS-362.a: Multi-Hazard Emergency Planning for Schools

- IS-15.b: Special Events Contingency Planning for Public Safety Agencies

- IS-29.a: Public Information Officer Awareness

Those who have taken earlier versions of these classes (with different suffixes) may submit those courses in lieu of the current editions.

IAP/ICS Forms Training

ICS forms published by FEMA provide a standardized template for cataloging and organizing incident information. Several of these forms are compiled together to create the Incident Action Plan. The information below is a brief guide on this, but specific training on how to create an IAP using the FEMA forms (or regionally-approved alternate versions) is required for the Silver Tier for anyone who might create an IAP for an incident, planned event, or exercise. FEMA offers an online Independent Study course (IS-201) on the forms. There is also an in-person course from TEEX (MGT-347) which may be offered in your area (contact your campus emergency manager or local or state OEM for information on whether this class is available in your area). To complete this requirement, you may also develop your own course or use a course developed by your campus OEM.

The ICS 201 is not typically part of an IAP, but does provide the baseline for the types of information in an IAP. The purpose of the ICS 201 is to provide an initial summary before a formal IAP is created. It can also summarize an IAP to allow an Incident Commander to more effectively preform a briefing to staff.

Most IAPs will include the following forms:

- The ICS 202 lists the Incident Objectives, or the high-level guidance from the Incident Commander. This list almost always includes one or two blanket objectives about life safety, incident stabilization, property conservation (more common during disasters like wildfires), and societal restoration (or a return to normal).

- The ICS 203 documents key personnel in various command and general staff positions. It is a written version of the key leadership, and is used to complete the organization chart on ICS 207. Note that the boxes on the FEMA template represent basic guidance, but because ICS is scalable and flexible, it is not necessary to fill all positions, and some areas may have more people than others.

- The ICS 204 is a template used to detail directions for specific elements of the ICS organization (most typically divisions or groups, but it can also apply to resource teams/task forces or even to single units). This form should be copied as many times as is needed for the scope and scale of your IAP. It can serve as a tear-out assignment sheet for the covered group/resources, and contains space for tactical instructions (more specific than the incident objectives from the ICS 202), special instructions, and the relevant subset of the communications information contained on the ICS 205.

- The ICS 205 is the overall communications plan for an incident. It details specific radio frequencies or talkgroups in use, their purpose, and other relevant information. During major incidents, the Communications Unit Leader (COM-L) will create this document in collaboration with other members of the ICS structure. It is also possible to have pre-filled versions of this form for various incident or event types where the relevant frequencies/talkgroups are already established by an existing policy or standard.

- The ICS 205A is a companion to the ICS 205, and covers methods of communication other than radios. In short, it is a list of phone numbers (or other contact methods) for individuals or groups in the incident. It is not included in all IAPs, but is a form that would be useful during an exercise or planned event.

- The ICS 206 is a medical plan covering injuries to responders. Though it is sometimes also used to document first aid stations for spectators at special events, its primary purpose is to let response personnel know how to get medical assistance if they themselves are injured. Under normal circumstances, information on the deployment of medical resources for the public at a special event is covered on the ICS 204 assignments for each team or supplemental planning documents.

- The ICS 207 is a visual representation (organization chart) of the ICS structure. It should contain similar names as the ICS 203. However, the FEMA PDF template is very rigid and likely will not be effective for most incidents. Therefore, if this form is used, you should utilize a flow-chart creation tool (like the SmartArt tool in Microsoft Word) to make a more appropriate chart. It is not always included in the IAP itself, but can be a useful component to better visualize the incident structure.

- The ICS 208 summarizes safety information for responders. It should cover key hazards and precautions that responders should observe. During special events, this often includes weather-related messaging (such as staying hydrated in summer), but for incidents, it would also cover how responders protect themselves from specific hazards (via PPE, mitigation actions, avoidance of certain areas, etc.). While not all IAPs require this form, it is recommended for most EMS agencies to ensure that their personnel remain safe. Certain elements of this form can be saved as templates, especially as they pertain to specific times of the year, weather patterns, and location-specific hazards.

Remaining forms are typically used as part of the formal "Planning P" process at large-scale incidents, but are not included in the final IAP itself. Many serve as "worksheets" to take specific information and develop more general statements that are used within the IAP (such as the ICS 215, which helps the Operations Section determine resource needs, or the ICS 215A, which helps the Safety Officer draft the ICS 208 Safety Message), while others help document incident tasks as they take place (like the ICS 214 which each unit or responder uses to document their activities, or the ICS 213 which communicates messages or requests between ICS components).

Some jurisdictions, agencies, or regions have developed their own variants of the FEMA ICS forms. It is acceptable to use those alternatives in your training class if that is what the standard is with your agency and those with whom you typically respond.

Emergency Operations Plans

There are two options presented at the Silver Tier for emergency operations planning: produce an EMS-specific Emergency Operations Plan (EOP) or ensure that your EMS organization is integrated into a campus-wide EOP. Determining which method to use will be based on discussions held at the level of your EMS organization and at the level of the campus administrator responsible for the campus-wide EOP. Input from outside EMS and emergency management partners may also be of assistance. If you opt to integrate EMS into a campus-wide EOP, we still recommend reading the EMS-specific EOP section below, as the guidance there may help you determine what additions are needed to the campus-wide EOP.

Developing an EMS-Specific Emergency Operations Plan

FEMA has a document called Comprehensive Preparedness Guidance 101 (CPG 101) which specifically covers developing emergency plans. While mostly aimed at state and local planning, the underlying information and practices in the document will also apply to specific departments of or organizations at colleges and universities. Reading through CPG 101 and adhering to its recommended practices will ensure that your Emergency Operations Plan is accurate and meets the needs of your organization. FEMA also has a document specific to Emergency Operations Plans for Institutions of Higher Education. In addition, reach out to your campus emergency manager (or other responsible administrator) as well as local government emergency management staff to let them know you are beginning this process, as they can advise if certain procedures need to be followed or if standardized plan templates are available.

Describe what creates an emergency for your organization. This should specifically indicate the difference between the routine response activities of your group and activities during emergencies or disasters. It is normally not necessary to list out specific triggers for specific hazards. Instead, consider what general conditions could lead to an emergency situation. This can also encompass situations where an EMS administrator or campus administrator declares an emergency.

Provide detail on how your organization's operations change during emergencies, including any special procedures, how your organization integrates with the campus organization, and what coordination steps will be taken. Remember the primary priorities for emergency incident response: life safety and incident stabilization.

With changes in operations come changes to roles and responsibilities for members of your organization. This includes updated organizational or command and control structures (for field response, this usually follows the National Incident Management System and ICS, while for EOC operations, alternate organizational charts are sometimes used). Your organization may also have additional duties assigned, or your responsibilities may be curtailed. These should all be described.

Under regular operations, your organization has certain abilities granted by the institution and local, regional, and state governing and EMS coordination bodies. In emergency situations, additional authorizations may be granted, or individuals may have modified authority. As an example, in local government EOPs, there is often a document signed by the mayor or chief elected official granting the Emergency Management Coordinator the authority to act on behalf of the city for certain specific emergency-related purposes. The EMS-specific EOP should include clear guidance on what additional authorities are granted, by whom, under what conditions, and for how long. The documents providing this guidance are called delegations of authority.

Your Emergency Operations Plan should also document (in general, since specifics sometimes change) what resources and facilities are available for emergency use. When those resources or facilities are not normally used by your organization, this is accomplished through written agreements with outside groups. As part of an academic institution, you may also be able to leverage the services of other departments (such as a facilities department) to handle this on your behalf. Discuss options related to this with the appropriate parties.

The plan should also include information on relationships with outside organizations. While your agency may utilize mutual aid on a regular basis, an emergency or disaster may change that relationship. In other situations, certain mutual aid agreements may only become active in a disaster (such as regional ambulance deployments). Be sure that these considerations are included.

As was the case with the MCI plan developed for the Bronze Tier, an EOP should include a timeline training on the plan and a process for plan revision. Your members need to know what is in the plan prior to implementing it. The plan should specify when and how training will be conducted. Training should always occur before the plan is used in an exercise, as this gives everyone the best possible chance of successfully implementing the plan and allows your exercise to highlight weaknesses in the plan (as opposed to exercising before training, which will only show you that training is needed). In addition, the plan should include guidance on how often revisions should take place. Plan revisions should incorporate lessons-learned and improvement steps from exercises and real-world activations. The process should also look for any changes inside your organization, at mutual aid partners, with laws or regulations, and to best practices as all of these can affect components of the plan. If the overall situation or environment in which the plan would be used changes, the plan must change too.

Governmental emergency management plans account for the financial and administrative concerns of disaster response for both the incident and the recovery process. Because disaster financial reimbursement may not apply to all collegiate EMS organizations (and because of the legal and administrative work necessary to prepare for it), this specific section is not required for EMS Ready Campus applications. However, it is advisable to have conversations with your institution about this issue if they wish to pursue the work needed in the future. Should you wish to pursue this component, know that while reimbursement is available for responses to disasters, that reimbursement is contingent on compliance with state and federal laws and regulations. Your institution's risk management, legal, and financial departments should be able to provide guidance, as can outside EMS providers who already are active in disaster response. At a basic level, you should be sure to include provisions for tracking hours worked by individual staff members (whether paid or volunteer), supplies and resources used and the costs of those supplies and resources, and damage to your organization's facilities and vehicles caused by the emergency. You should also ensure that your members are all compliant with NIMS training requirements. And be aware that disaster reimbursement is often based on your organization's normal costs, so expecting financial reimbursement for hours worked by EMTs when their normal activities are done on a volunteer basis is not realistic. That said, hours spent volunteering in response to a disaster can sometimes be used by local governments as credit towards their federal cost-sharing requirements, so tracking the services of volunteers is still important.

After drafting the EOP, it should be reviewed by outside individuals. It is recommended that you start with your institution's emergency manager (or the equivalent administrator). Then provide the plan for review by any other campus departments that are referenced in the plan to ensure that they are aware of what you expect from them. They may provide feedback that the expectations cannot be met, in which case the plan will need to be revised. After working internally at your institution, provide the EOP for review by outside partners referenced in the plan, again incorporating any feedback they provide. Finally, get feedback from governmental emergency management partners and regional or state EMS coordinating groups. This process will ensure your plan does not conflict with other plans while also helping you gather valuable feedback from others who may have broader emergency management experience.

Incorporating EMS into your Institution's Emergency Operations Plan

As an alternative to developing an EMS-specific Emergency Operations Plan (EOP), your organization may decide to ensure EMS is incorporated into the campus-wide EOP. If this alternative is selected, certain EMS Ready Campus application requirements will change, but the overall content issues discussed above for a stand-alone EOP will still apply.

First, incorporation of EMS into a campus-wide EOP should involve a series of conversations between EMS and campus administrators responsible for revisions of the campus-wide EOP. In addition to ensuring that the campus-wide EOP has specific roles for EMS that are realistic (neither too broad or too narrow), the conversations should also ensure that EMS operations will fit in appropriately with campus-wide incident command, that EMS is afforded similar input in a unified command setup as other departments (such as law enforcement and campus health), and MORE?

Second, the information about EMS identified in the first step should be integrated into the campus-wide EOP. This can either be done in a section specific to EMS, or in existing areas of the campus-wide EOP as appropriate. In some cases, the existing campus-wide EOP may already be sufficient. For the purposes of the EMS Ready Campus application, you should submit one of the following, depending on which route your institution decided to go:

- if an EMS-specific section was added to (or already existed in) the campus-wide EOP, submit the EMS-specific section;

- if changes were made throughout the existing campus-wide EOP, write a detailed summary of the changes made; or

- if the campus-wide EOP already included EMS, write a detailed summary of the existing information in the EOP that relates to EMS.

Third, your organization needs to formally adopt the campus-wide EOP. You should draft a policy which reflects this, and also ensure that staff are trained on the applicable sections of the campus-wide EOP in the same way they would be if your organization drafted its own EMS-specific EOP. Documentation of the adoption policy and training requirements should be submitted with your EMS Ready Campus Application.

Fourth, your campus emergency manager (or equivalent administrator) should provide a letter certifying that the campus-wide EOP incorporates your EMS organization at an equivalent level to all other campus departments, that they have met with EMS leadership to ensure that expectations are realistic, and that EMS will be included in the incident command structure as appropriate to a given event or incident. This letter should also be submitted with your EMS Ready Campus application.

Hazard Vulnerability Analyses

In this Tier, you will build upon the hazards selected in the Bronze Tier and begin to add more detail that you can then use to guide your planning, training, and exercise activities. Go line-by-line through each hazard on the worksheet and provide an honest assessment of your group's capabilities. This is a subjective assessment, but the value in this activity is helping you identify activities that your organization can continue to use to improve its operations. As you fill out the sections of the HVA Worksheet for the Silver Tier, you will find several boxes that have drop-down options. Please use the guidelines below to select your responses.

- Plan

- Yes (Specific Plan Exists) should be used when you have developed a stand-alone plan or annex for this particular hazard. For example, schools along the Gulf Coast may maintain a dedicated Hurricane/Tropical Weather plan.

- Yes (Fully Covered by General Plan) should be used when the response to this hazard is fully covered by your group's standard EOP or other existing (generic) document.

- Yes (Partially Covered by General Plan) should be used if your group's standard EOP or other existing (generic) plan partially covers the response to this hazard, but additional updates may be needed to fully address the planning needs.

- Planning in Progress means that you are working on developing a specific plan for this hazard or updating your group's standard EOP or other existing (generic) plan to better cover this hazard.

- No should be used if you do not have any plans that address the response to this hazard.

- Training

- Regular Training is Conducted should be used if you routinely train personnel on responding to this hazard (ideally with training objectives taken from your plans relating to this hazard). It is up to you as to what constitutes "routinely," but it is assumed that if you select this option, you feel that your personnel do not need additional training to competently respond.

- Some Training is Conducted should be used if you occasionally train on responding to this hazard, but feel that additional training would be prudent.

- None should be used if you do not provide training on responding to this hazard.

- Supplies

- Yes should be used if you feel that you have the right type(s) of supplies/equipment and have those supplies/equipment in sufficient quantities to respond to this hazard and the anticipated number of patients it could produce. An example would be having enough triage tags (or wristbands), bandages, red/yellow/green tarps or flags, and backboards/litters to properly triage and prepare patients for transport in an MCI.

- Have Appropriate Equipment but Not Sufficient Quantity should be used when you have the right type(s) of equipment/supplies, but not enough of them to handle the anticipated number of patients. For example, if you want to prepare for an active shooter, you may have one or two tourniquets and packages of clotting bandages, but not enough to handle the anticipated number of casualties.

- Have Sufficient Quantity but not Appropriate should be used when you have enough general supplies for the anticipated number of patients, but lack certain specialty equipment/supplies, or the equipment/supplies you have are not of the type best suited for this particular hazard. In the case of the Vehicle Ramming Attack (where patients with various fractures would be anticipated in addition to lacerations), you may have large quantities of bandaging material and c-collars, but you lack flexible splints and pelvic binders for the specific injury types anticipated from this hazard.

- No should be used if you feel you do not have the proper quantities or types of supplies for this hazard. For example, if your campus has a day care center and you determine that a Croup outbreak is a hazard your campus faces, lacking any amount of nebulizers or racemic epinephrine (a nebulized medication used to treat Croup) would mean that you do not have the quantity or types of supplies needed to properly respond to this hazard.

The Gold Tier will require you to begin taking steps to address these gaps, and the best time to start planning for those steps is now. The likelihood and impact assessments from the Bronze Tier can help you prioritize the order in which you address the gaps, but it is also acceptable to address easy-to-close gaps before you address ones that require more effort, cost, or planning.

Continuity of Operations

The requirements of this Tier are meant to build upon work done during the Bronze Tier. First, ensure you have acted upon any feedback from your Bronze Tier submission regarding the types of tasks you cataloged and the documentation of responsible individuals and successors. Check these new and existing documents to ensure the data remains accurate.

At this point, it is recommended that you begin soliciting feedback from the person or group on your campus who handles campus-wide COOP plans. At a college or university, this person or group may fall into one of the following departments or categories of staff:

- Business Continuity

- Risk Management

- Administrative Services

- Emergency Management

For S.G.1, we ask that you get basic feedback on the tasks you have identified and your documentation of responsible individuals/positions and successor individuals/positions. This is meant to ensure that you are accounting for all the key tasks that you should be, as well as to help align the work being done for EMS Ready Campus with your campus’s procedures for COOP planning. Use the feedback from your campus COOP personnel to make any necessary updates or changes.

At the same time, S.G.2 asks you to build upon the work of the Bronze Tier and begin to document how to do each task. By writing down procedures (including referencing any outside resources needed), you’ll provide a blueprint for someone who may need to step into a role on short notice.

You should not reinvent the wheel here. First, look at what job aids and other documentation already exist. In the example case of the EMS organizational license renewal, does your state licensing agency already have a checklist for this? Or in the example of the crew chief’s review of patient care reports, what documentation already exists from your field training or new crew chief training program? Utilizing existing resources (either internal or external) is encouraged when completing this requirement.

When submitting this section, you should provide a summary listing of the different tasks identified, but complete detail is not needed for all tasks. Instead, select one to submit as an example, showing the task name, Primary and Supporting individuals/positions, Successors, and the task directions/job aid.

Gold Tier

The Gold Tier is the highest level of recognition in the EMS Ready Campus program. Organizations that receive the Gold Tier should not only be fully active in emergency management but should also be capable of serving as mentors for organizations applying for lower tiers. As such, applications at this tier will be evaluated with the highest level of scrutiny.

Pre-Filled ICS 205

During a Mass Casualty Incident (MCI), reliable communication can be difficult. This process becomes more difficult considering that while many collegiate EMS agencies respond with one or many mutual aid partners during normal incidents, the number of outside agencies increases even more during an MCI.

One way to address communications challenges is to pre-determine radio channels or talkgroups amongst responding agencies. By knowing in advance which functions are assigned to which channels/talkgroups, the confusion at an incident scene can be reduced, and the Incident Commander has one less decision to make in the heat of the moment.

If a document of this nature already exists for your region, you may submit that (but verify that your agency has access to all the referenced channels/talkgroups, and if not, make efforts to close this gap). If your region does not have a document of this nature, then you will need to develop one.

When making determinations on which channels/talkgroups to assign to specific functions, it is important to start with what needs its own channel/talkgroup during an MCI. These are your communications needs. Also speak with the other agencies who would respond with you during an MCI to get their input. The goal is to create a document that will work seamlessly for all involved parties, not just your agency on its own.

From there, catalog existing channels/talkgroups used for incident communication (tactical or mutual aid channels/talkgroups) as well as regional shared channels/talkgroups intended for emergency incidents. These will represent your available communications resources. Again, work with other agencies (as well as any regional radio network administration groups, if such groups exist in your area) to determine if any of these channels/talkgroups would already be in use during an MCI so you can avoid including them in your document.

After you have identified your communications needs and available resources, you can then begin assigning functions to specific channels/talkgroups on your ICS 205 form. Socialize the completed form with all other response groups involved in the process (as well as your regional radio network administrators, if such a group exists) and have them check to make sure that the document would not conflict with other established communications plans. Once this has been verified, then you will have developed a pre-filled ICS 205 suitable for use during an MCI.

Training

Most training requirements for the Gold Tier are specific to your campus. See the application checklist for details. That said, additional training is specified for certain members of your organization as noted below. In addition, remember that anyone who has joined your organization since the Bronze and Silver Tier trainings were conducted must also complete those classes.

Additional Training for Leadership

Additional training is required at the Gold Tier for anyone who may assume a command role on an incident scene as well as listed members of your organization's leadership team. Based on the content of the courses and your organization's internal procedures, you may also wish to assign these courses to additional members as you see fit.

- ICS 300 is a free three-day in-person course. Contact your local or state emergency management agency for information on upcoming offerings.

- The FEMA Professional Development Series (PDS) is a certificate issued after completion of seven Independent Study courses. The process is free, but issuance of the certificate takes additional time. The actual Professional Development Series certificates must be submitted for the EMS Ready Campus application (not simply the completion certificates for individual courses). Full details are at the FEMA website.

Additional Training for Exercise Design and Evaluation

Individuals in your organization involved with exercise design and evaluation should complete two additional free online FEMA independent study courses. Note that one of these overlaps with the requirements for the PDS certificate.

HSEEP-Compliant Exercises

The Gold Tier places additional requirements on the use of exercises to support emergency management and emergency response. FEMA has compiled best-practices on exercises into the Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program (HSEEP). Full information on the HSEEP process is available via in-person FEMA courses on the program (contact your local or state emergency management agency for details). However, the overall point of the program is to ensure that exercises are conducted using best-practices like utilizing a planning process when designing an exercise, developing SMART exercise objectives, having clear guidelines for exercise outcomes and evaluations, using a stair-step approach to exercises (start with training, then proceed to smaller or task-focused exercises prior to conducting large and more complex exercises), and conducting after-action analyses and generating improvement plans based on exercise results. In addition to the educational content provided during an HSEEP course, FEMA also provides an HSEEP Toolkit that contains templates that can be used for exercise documentation. That toolkit is available for free from the FEMA Preparedness Toolkit site.

If possible, you should also solicit the guidance of a Master Exercise Practitioner (MEP) to assist with designing your exercise. FEMA's MEP program is intended for experienced emergency management professionals who wish to gain an in-depth knowledge of exercise development and execution. As this program requires specific experience, includes an application process, and has mandatory in-person training at FEMA's Emergency Management Institute, it is not recommended for current students. However, you should encourage a member of your school's administration who is involved in exercise development to pursue the certification to ensure your institution benefits over the long term.

Hazard Vulnerability Analyses

In this tier, you are expected to have begun to close gaps identified during the Silver Tier. As you perform this work, track your progress to allow you to complete G.F.1. There is a column in the HVA Worksheet that you used in the Bronze and Silver Tiers to allow you to note gaps as you close them. This is for your internal purposes but your responses to G.F.1 should be in narrative format.

For gaps that remain, provide documentation as to why they remain open and what steps you have taken or plan to take in order to address those gaps. For example, you may have opted to address the gaps that were easiest to close first. However, your efforts to create a plan for a specific hazard may require work with other campus partners and the process is awaiting their input. You are not being graded on the number of gaps addressed, but for successful completion of the requirement, you do need to show that you are making an effort to address the issues identified.

Hazard Vulnerability Analyses

Completion of a full COOP Plan (or squad-specific annex to the Campus COOP Plan) is not required by this program. Full COOP plans require additional elements not covered under the EMS Ready Campus program. Instead, the requirement at G.G.1 is just to solicit detailed feedback from campus staff responsible for COOP planning that will help guide your future continuity planning activities.

This discussion should also cover what additional information they would need from you to either help you create your own COOP Plan or add a squad-specific annex to the Campus COOP Plan. Your response to this criterion should be to summarize the results of this meeting, to include additional steps you plan to address in the future based on the feedback received.